Almost exactly four hundred years ago, drifting ice on the river Lek outside Utrecht smashed up a dike on the Rhine distributary. It was a disaster in a country that is one-thirds below sea level. Soon, the entire region was flooded, with even Amsterdam threatened.

However, the Dutch were brilliant, sophisticated pioneers of finance, and knew exactly what to do. In January 1624 the local water board - called Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams - sold a 1,200 guilder bond to a wealthy woman in Amsterdam called Elsken Jorisdochter. In return for the money to finance immediate repairs, the water board promised Jorisdochter, her descendants or anyone who owned the goatskin bearer bond 2.5 per cent interest in perpetuity.

The dike is still there, in a bend of the Lek river. Even more remarkably, this bond is still alive. It first paid its interest in Carolus guilders; then Flemish pounds; then modern guilders and today the Hoogheemraadschap De Stichtse Rijnlanden – a Dutch utility that is the legal descendant of the original water board – pays its current owner the New York Stock Exchange about €15 of interest a year.

Here you can see it displayed at last year’s Fixed Income Hall of Fame dinner, next to some gawping, awestruck bond groupie.

Just think about what this bond has survived.

The borders of the country now called the Netherlands have changed many times. There have been multiple revolutions and religious revolt. Napoleon subsumed it entirely at one point. There have been two world wars, several pandemics and four currencies. And through it all, it has kept paying interest.

So why am I banging on about this? Well, partly because I think this is amazing. It is a genuine financial wonder of the world. If you don’t like a four century old Dutch goatskin perpetual that still pays interest then I’m afraid we can’t be friends.

But mostly because it is a physical reminder of how bonds built the modern world. They have won wars and broken countries, funded hospitals and medicine and tobacco farms and sugar plantations. Bonds paid for the Louisiana Purchase, and what we watch on Netflix. And they are eating up more and more of the financial system.

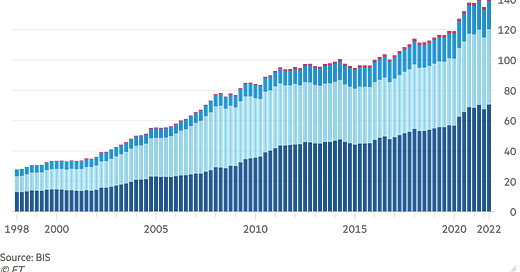

A few years ago I spotted a fascinating factoid buried in a typically recondite BIS report: for the first time in history, over half of all debt was in the form of bonds rather than bank loans. Excited, I wrote a column, because you never let a good factoid go to waste.

Of course, like many factoids it had some hair on it. I later learned that the BIS data weirdly doesn’t seem to include mainland China, for example. The latest BIS data puts the global bond market at $141tn, while the Financial Stability Board estimates the size of the banking industry (including mainland China) at $183tn.

However, a large chunk of bank assets are actually IN bonds, not traditional loans. I have yet to find a comprehensive global dataset on bank loans, but I feel pretty confident saying that the bond market today does more lending than the global banking industry (in fact it plays an integral role in funding banks, to the tune of $50tn at the end of 2022).

The implications are enormous. Yes, bonds and loans are both fundamentally different forms of debt. For simplicity we often just treat debt as debt, whether it is in the form of loans or bonds. David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years hardly mentions bonds. But form matters.

For centuries we have always thought of banks as the focal institutions of modern capitalism. Everything flowed through them. It is why banking crises have proven so diabolically painful. But gradually, bonds have encroached upon and gradually supplanted banks from more and more of the credit machinery that powers the global economy.

Government debt was the first to fall. Almost all countries nowadays finance deficits solely through the bond market. But over the past century the corporate bond market has expanded rapidly, and with the development of the high yield market since the 1980s it is no longer the sole preserve of huge lumbering corporate behemoths. Securitisation might still be a dirty word after the 2008 financial crisis, but it has meant the bond market is now a major player in mortgages, credit cards and auto loans in the US – and Christine Lagarde (rightly) wants to see the same in Europe.

Ok maybe I am blinded by my love for the bond market. My first job as a journalist was writing about sukuk — Islamic bonds that used legal and financial finessing to get around the Muslim prohibition against interest — and as Cat Stevens sang, the first cut is the deepest. I still fondly remember talking to some of the world’s leading sharia scholars about the intricacies of Ijarah (a sale and leaseback structure) and Murabaha (cost-plus-profit margin sales).

But I think this bank-to-bond shift is both historically fascinating and hugely meaningful. At the very least can already see how the nature of financial crises is morphing, and with it the role of central banks.

Luckily the fine folks at Penguin Random House agree with me. They’ve bought the rights to a book on the subject – working title THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH - which I hope to finish later this year. If you can’t wait, I adapted the book proposal for an FT Weekend Magazine cover story, which you can read here. And if you want to know a little more about the Dutch perpetuals, I wrote about it for FT Alphaville here.

Speaking of Alphaville, here’s what we got up to this week. A reminder that all this is FREE, you just need to register with an email to read FTAV.

– Death and snackses. You can tell Louis had a lot of fun going through the Walkers’ Sensations Poppadoms vs HMRC judgment. I dare you not to crack up at nominative determinism bit.

– The Bitcoin ETF saga. If spot bitcoin ETFs are so great, why’s the bitcoin price down?

– Business Development Companies. There have been a spate of BDC IPOs lately, but the trend is towards private, nontraded ones because no one likes volatility.

– Laser-eyed Ben Franklin. I get that Franklin Templeton needs to reinvent itself, and maybe I’m just a die-hard crypto sceptic, but this drove me crazy.

– Watches of Switzerland. And what it says about demand for Rolexes.

– BP rumours. So many rumours. Pity the poor M&A journalists that have to follow this all the time.

– The IMF’s fave pupil gets another gold star. I’ve been fascinated by Jamaica’s economic story for over a decade now, and the Fund’s latest (virtual) visit was an excuse to take another look.

– China’s next big export. A lot of people think it will be deflation. But how meaningful are falling Chinese export prices really?

– Swap spreads. A wonderfully geeky deep-dive into why UK swaps trade (sharply) inside gilts by Toby Nangle. The post image is enough to make it worth checking out.

– US recessionwatch. Alex dove into the hows and whys of the bond market pricing in a lot more Fed rate cuts than the Fed and economists say are coming.

– But what if we don’t get those rate cuts? Louis asks the question no one wants the answer to.

– Chart misdemeanours. Goldman Sachs has a reputation for the fastidiousness of its powerpoint presentations, so this caught our eye.

– Private credit. Here’s an interesting way of estimating how many defaults there actually are in the burgeoning but opaque private credit market.

– Liberumanure. The City of London’s new subscale stockbroker.

– Morgan Stanley’s block trading penalty. Even allowing for what the Fed said was “extraordinary cooperation”, the investment bank arguably got off lightly with just a $249mn fine.

– Quant factor aggro. No one does passive-aggressive better than financial academics.

– And finally, the UK’s strategic wine reserve. REALLY!

Looking at all this makes me wonder if I should send out BTD a bit more often, so it doesn’t become an overlong linkdump. But given the book project (and the three hellspawn) I’m not sure I can cope with more frequent missives. And I’m guessing you are all already bombarded with newsletters?

Can't wait to read your book, and honestly looking forward to more missives from BTD, as they are one of the best, if not the best subscription related to the financial world. Thank you Robin.

Looking forward to reading the new book! Actually, I'm just about to read Trillions too.